Dog Anatomy

Dog Joint Anatomy

The anatomy of dogs varies tremendously from breed to breed, more than in any other animal species, wild or domesticated. Yet there are physical characteristics that are identical among all dogs, from the chihuahua to the giant Irish wolfhound.

They have small, tight feet, walking on their toes; their rear legs are fairly rigid and sturdy; the front legs are loose and flexible, with only muscle attaching them to the torso. Dogs have disconnected shoulder bones (lacking the collar bone of the human skeleton) that allow a greater stride length for running and leaping.

Bones and Joints of a Dog

The forelegs and hind legs of a dog are as different as human arms and legs:

- The upper arm on the foreleg is right below the shoulder and is comprised of the humerus bone. It ends at the elbow

- The elbow is the first joint in the dog’s leg located just below the chest on the back of the foreleg

- The long bone that runs down from the elbow of the foreleg is the forearm. It is comprised of the ulna and radius

- The wrist is the lower joint below the elbow on the foreleg

- The upper thigh (femur) is the part of the dog’s leg situated above the knee on the hind leg

- The stifle or knee is the joint that sits on the front of the hind leg in line with the abdomen

- The lower thigh (tibia and fibula) is the part of the hind leg beneath the knee to the hock

- The hock is the oddly shaped joint that makes a sharp angle at the back of the dog’s leg (corresponds to a human’s ankle)

- Often called the carpals and pasterns, dogs have them in both forelegs and hind legs (equivalent to human bones in hands and feet – excluding fingers and toes)

Joint Anatomy in Dogs

A joint is formed when two bones are brought together and held in place by supporting tissue. Joints may have ranges of movement such as the shoulder and hip joints, or have very little movement such as joints between the bones in the skull.

There are three types of joints based upon the type of tissues that connect the bones:

- Synovial Joints – Generally have the greatest range of motion. In a synovial joint, the bone ends are covered with cartilage. Tough, fibrous tissue encloses the area between the bone ends and is called the joint capsule. Ligaments hold the bones in alignment. The ligaments may be part of the joint capsule. The inside of the joint capsule (the joint cavity) is filled with synovial (joint) fluid.

- Fibrous Joints – Allow very little movement. Joints are held together by tight fibrous tissue. The joints in the skull are fibrous joints

- Cartilage Joints – Allow some movement and are formed when two or more bones are joined by cartilage. The joints formed between each vertebra in the spine are cartilage joints

In synovial joints, resilience of cartilage tissue is important for normal motion as well as shock absorption. Hyaluronic acid provides lubrication to the synovial membrane surface and together with another protein, lubricin, it also lubricates the articular cartilage.

Joints in the Dog

Carpal Joint – The carpal (wrist) joint is where the radius and ulna join with seven small carpal bones. From the carpal bones ensue five metacarpal bones which connect to the bones of the foot, termed the phalanges. In addition to its structural functions (keeping the dog from falling and facilitating locomotion), this system of joint and bones is capable of performing both generalized and highly specific movements. Ankylosis (stiffness of a joint due to abnormal adhesion and rigidity of the bones of the joint) of the carpal joints can be exceptionally negative for the dog, seriously limiting standing capacities and lateral locomotion.

Elbow Joint – Formed between the distal end (farthest) of the humerus and proximal end (nearest) of the radius and ulna. Elbow dysplasia is a disease of the elbows of dogs caused by growth disturbances in the elbow joint. This is due to a mismatch of growth between the radius and ulna which damages the cartilage in the joint and can lead to fractures within the joint. Dogs with elbow dysplasia are often lame or they have an abnormal gait.

Stifle Joint – The stifle (knee) joint of the dog is a complex joint that combines sliding, gliding and rotation as the joint flexes and extends. This joint in the hind limbs of dogs is often the largest synovial joint in the body. The stifle joint joins three bones, the femur, patella and tibia. The complexity of the motion of the joint is an indication of problems that can occur through injury to this joint. Ligament injuries are common and fractures of the knee joint include fractures of the patella, distal femur and proximal tibia.

Hock Joint – The hock (ankle) joint connects the paw (talus and calcaneus bones) to the shin bones (tibia and fibula). This joint is held together by a set of ligaments primarily located on the inner and outer sides of the joint. Hock instability can occur due to tearing of ligaments that hold the bones of the hock in place, or bone fractures. Hock instability results in a sudden onset of lameness. Pain, swelling and heat associated with the affected joint are indications of the condition.

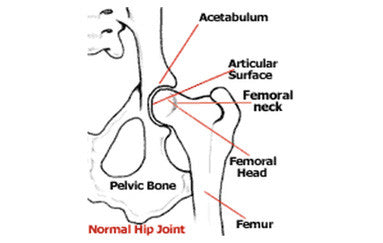

Hip Joint – In the normal anatomy of the hip joint, the almost spherical end of the femur head fits into a concave socket in the pelvis (acetabulum). Normal hip function can be affected by congenital conditions such as dysplasia, trauma and by acquired diseases such as osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis. Hip dysplasia can be caused by a femur that does not fit correctly into the pelvic socket or poorly developed muscles in the pelvic area. Larger breeds are most susceptible to hip dysplasia. Causes of hip dysplasia are both hereditary and environmental (overweight, injury at a young age, overexertion of the hip joint at a young age and ligament tear at a young age). The problem almost always appears by the time a dog is 18 months old. It is most common in medium-large pure bred dogs, such as Newfoundlands, German shepherds, retrievers (Labradors and goldens), Rottweilers, and Mastiffs, but also occurs in smaller breeds such as spaniels, pugs and dachshunds.